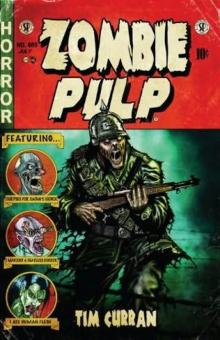

Zombie Pulp Read online

Page 6

“What cause is that, boy?”

“Freedom for my people, mister, what else?”

Riker thought that was hilarious. “Freedom? What fucking freedom, boy? You a convict, case you didn’t notice. We all work for massah here. We all just trash society put out to the curb.”

Johnny told him that was certainly true.

And then Riker admitted he was doing life for multiple homicide. Had waltzed into a bank, planning to rob it. Guard saw him and went for his piece, so Riker drilled him and then, feeling funny that day, he killed four more people so they wouldn’t be able to identify him.

“My head was full of kitty litter back then, boy,” Riker told him, “and I ain’t so sure they’s not a few turds still stuck between my ears even now.”

Stories told, Riker gave him the grand tour.

Took him down that grim concrete block corridor that smelled like wet steel, tears, and pesticide, showed him the freezers. Behind iron doors, bodies crowded under stained white sheets, arms hanging out all gray and blotched from lividity. Riker showed him the cold cuts, how bad it had all been. Here a couple blacks with slit throats, there a Hispanic that had been kicked to death so that his jaw was planted by his left ear now, and here some dumb white guy who’d decided to intervene and had his head split clean open. The dumb and the dumber. In the drawers, no better. Eyes punched out and faces erased and bones sticking through dirty canvas skins like broomsticks.

Then Riker showed him the garage out back where all the caskets were piled up-cheap pine things hammered together in the carpentry shop.

“They two kinds of dead here, boy. Them what get claimed by their kin and them what end up out in potter’s field. Most of these boys will end up out there on account they families is ashamed of ‘em.”

Back in the office, Riker parked Johnny at the desk, gave him some fuck books and a few paperback westerns, told him to just pass the time, keep the doors locked. That was it.

Then he gave him a Thermos of whiskey.

“Drink your fill, boy,” he said. “A little taste is one of the benefits of sorting out the dead ones and they troubles.”

*

But now Johnny was alone.

Riker said he wouldn’t be back before first light.

Thump, thump.

No foundation settling or walls groaning, this was something else. Something bad. Something big and angry that did not care to be ignored. Johnny kept telling himself that there was a very good reason for what he was hearing. Maybe some con had gotten himself bagged up alive or such…but he didn’t believe that.

Sucking in a sharp breath and wiping cold sweat from his forehead, he went to the door that opened into the corridor. He touched it with his hand. Cold, damn cold was how it felt. He could feel that cold seeping in through his pores, locking down everything within him in a blanket of ice. He could hear that damn clock ticking and the blood rushing in his ears.

He heard the sound again and his heart hitched painfully in his chest.

Something, something alive back there.

His face was tight as cellophane against the skull beneath, the flesh prickling unpleasantly at the back of his neck. Sweat ran into his eyes and he shivered and breathed and licked his lips slowly, slowly, feeling a sudden rushing weight settle into him and knowing it was madness. That insanity had a physical, ominous presence. His eyes studied the door, bulging and white and unblinking.

All right, then, all right.

His hand found the doorknob, eased it open. A well of shifting, damp blackness billowed out at him, fell over him, got up his nostrils and down his throat, tasted like wormy coffin silk on his tongue and stank of wet, dripping crypts. He turned on the light switch before that blackness suffocated him, drained him dry, whisked him off into the freezer like a chop put up for next Sunday’s cookout.

There was a single light bulb and it created crawling shadows, made things even worse.

Outside the freezer room, staring at that riveted iron door painted the color of old blood and thinking it was like the door to some old vault, Johnny listened, brought his fingers to the latch.

Sound in there…not that thumping, but a whispering sound.

Johnny’s breath clogged in his throat like grave dirt.

Open it, open it for chrissake.

The latch sounded like thunder in the corridor, clanking and groaning. The door opened soundlessly. Johnny’s fingers-twisting whitely now like worms dying in the sunlight-found the old-fashioned switch and brought light into the world.

Nothing.

The drawers were all closed, the slabs still occupied, the gurneys still squeezed in-between and all available floor space was thronged with shrouded figures waiting for burial.

Johnny’s fingers put a cigarette in his mouth, lit it.

He took a deep, long pull, knowing what he needed here was some strength, some balls and not those playground marbles that had sucked up into his body cavity.

The freezer room was green-tiled, stank of dirty backwaters and quarry slime, vomit and frozen meat. Johnny went in there, stepping over and around the ones on the floor, pausing-for reasons he was even unsure of-before a slab.

His heart thudded dully in his chest.

He took hold of the sheet like the page of a book, pulled it back carefully, a chilly earthen smell coming off the body. Most of the flesh was missing from the face, what was left an ashen gray speckled with dirt and dried blood. A bullet had gotten this one and a high-caliber by the looks of it. Tower guard. Gums were shriveled away from teeth, the left eye blown clear away with its attendant orbit of bone. The right eye was open and staring, glazed over.

There was something nestled on the chest.

Johnny thought at first it was some big spider…but no. Just a little figure molded from black mud and sticks. Like a little doll. How in Christ did that get there? Johnny dropped the sheet, checked two more bodies. No dolls. But a third had one and so did a fourth.

What the hell were they? What was going on here Thump, thump, thump.

From the drawers then. Like something in there was trying desperately to get out, hammering and pounding. Johnny went cold, went hot, felt his skin crawl and a tornado of white noise whip through his brain.

Something was happening now. There was a cool, crackling electricity, a sharp smell, a motion, a sentience, a heavy thrumming awareness. Johnny’s mouth went dry as sawdust, he could not open his lips-they had been sewn shut.

He stumbled back, fell over a body, his hand brushed a fleshy arm that felt like thawing beef. He sat there on his ass, unsure, unknowing, unable to do much but shake and gasp and wonder. He could not move, could not breathe. The drawers-many of them now-thumping and banging and rattling in their housings. Their metal faces were bulging, dented out from the inside.

Then all around him, as if stirred by some secret malefic wind, sheets began to tremble and rustle and shift with motion beneath them. Arms slid out, fingers clutching madly in the air like snakes.

Johnny heard a voice whisper, another grunt, another make something like a dry barking sound. He sat there, suppressing a demented desire to start giggling. The bodies were sitting up now, sheets sliding from gray, bloodless faces and bodies like sloughed skins. Shadows crawled up from the corners, twisted like thick serpents, hissing and slithering.

A voice as brittle as crunching straw said: “Watch out, George…that sumbitch got a big knife he…”

But the others were talking now, too, speaking in those dry voices that were merely snarling, guttural noises that made Johnny want to scream. They were like cold steel at his spine, the flats of knife blades dragged along his belly and groin. Echoes. Just echoes. That’s what they were. The worn spools of those decayed brains repeating and repeating their final living thoughts until the room was alive with a ghastly murmuring.

They had risen up all around him now.

Grinning, frowning, smirking. Those faces were hideous moons with ragged, black impact craters f

or eyes. A dozen morgue drawers burst open, slid out on squeaking casters, sheeted forms rising, fingers twisting and tearing at their shrouds. Oh and dear God, those eyes-blanched and discolored, staring and hollow and so utterly empty.

The dead were on their feet now, stumbling and staggering and shambling. Some were naked, others clothed in bloody prison issue or filthy hospital gowns.

Johnny crawled on hands and knees out the doorway and they followed, a ragged, grisly throng of chattering teeth and wiggling fingers and whispering voices. Ligaments popped like rusty hinges. Muscles snapped and bones splintered. They stank of tombs and drainage ditches and body pits. One of them looked at Johnny, tried to speak, but a flood of black bile oozed from his lips, hung from his jawline like ribbons of mucus. His voice became a bubbling, gargling sound.

Screaming, Johnny found his feet, scrambling madly not towards the office, but to the garage and the outside door. His fingers had gone stupid and numb and rubbery and he could barely work the lock, barely throw himself into the black wet night before they were on him. Shouting and hollering, he fell out into the rain, coming to rest in a muddy pool. Thunder rumbled in the sky and lightening flashed, painting the landscape in lunar brilliance.

They had not followed him.

Johnny sat there in the muck, rain pounding down on him. The air was cold, but the mud around him was warm and sluicing like blood. He looked frantically off towards the prison itself, could see the high towers, the buildings, the wall…but not much else.

The whispering throng was coming out now.

They paid no attention to Johnny.

Balanced atop their shoulders, they carried caskets. Single file, they pushed through the muck and rain with their coffins, a funereal parade of contusions and slit throats, stab wounds and shattered skulls. A collection of stiffly animate rag dolls trailing stuffing from snipped stitches, bearing torn limbs and dangling shoebutton eyes. And making, yes, making for potter’s field. At least thirty of them, keeping an almost military cadence.

Johnny sat there for awhile, drenched and dirty and shaking.

The rain fell and the susurration of the ghouls faded into the distance and although Johnny wanted to run and run, he could not. He got to his feet, brushing mud from his arms. Then he followed them, knowing deep down he had to see this.

Through the swampy, sunken landscape he went until he caught sight of them gathered at the far side of the cemetery. In the flashing lightening, he could see they were working. Yes, they had shovels now. Dead men digging their own graves and not slowly, mindlessly, but with great effort and concentration.

Johnny could see there was someone with them.

Someone with a flashlight barking out orders.

Johnny came forward and soon enough saw Riker there, yelling at the dead men, kicking dirt at them, drumming them on the heads with the barrel of his flashlight. “Dig, you bastards!” he was screaming at them. “Dig, dig, dig! Dig ‘em down deep, you know what you have to do! You know the way!”

Johnny, wordlessly, stood by the mortuary boss for some time, watching the gray rain-swept figures digging and widening and squaring off their holes. When they were done, they lowered their caskets down…and climbed into them. Within a half-hour, all the graves were dug and the last of the lids slammed shut with a brutal finality.

Then there was only silence. The sound of rain, distant thunder.

Riker, his face wet with rain, said, “See, boy, how it works is, the guards, oh they love me, on account I handle the mortuary so they don’t have to. I see that the dead are registered, the graves dug and filled and I do it all by myself. I do it with them.”

“Dead men,” Johnny managed, his mind drawn into a soundless vacuum now. “Living dead men.”

Riker clapped him on the shoulder. “That’s it, boy! That’s it exactly! See, years ago, when I started at the mortuary they was this Haitian fellow ran it, a drug dealer. He taught me about the walking dead. Corps Cadavre, he called ‘em. He showed me how it was done. How to make the powder, the dolls, to make with the mumbo-jumbo ju ju talk-”

“Zombies,” Johnny found himself saying incredulously. Because that’s what they were. Dead men summoned up to dig their own graves. Just like the dead men you heard about, worked those cane fields in Haiti and Guadeloupe and those places.

Riker gave him a shovel and for the next hour or so, they filled in the graves, marking them with simple wooden crosses. Then it was done and they both stood there in that dank cold, in that brown sloppy soup of mud.

“Boy, you’d drank that whiskey like I told you,” Riker said, “you’d have slept right through all this, see? I put enough seconal in there to put you into dreamland for six, eight hours.”

Sure. That’s why he didn’t want anyone in the mortuary that night, things had been all set. The cadavers that hadn’t been claimed were given that powder and the little dolls, told when they were to open their eyes and get to work. It was almost funny…if it hadn’t been so damn depraved, so horrible and, yes, disgusting.

Zombies, Johnny’s brain thought, zombies.

Empty as a tin can, he turned away from Riker and that was a mistake.

Riker hit him with a shovel, opening his head. Johnny sank into the mud like a drowning man. Fingers of gray slop ran from the open crown of his head.

“Sorry, boy,” Riker said, “but I can’t have you telling what you saw.”

Taking Johnny by the feet, he dragged him back towards the mortuary, wondering what sort of story he might concoct. Figured it would be a good one.

*

Two nights later.

The prison mortuary.

A morgue drawer.

Tagged and bagged, Johnny Walsh lay in his berth in that cool, easy darkness. His hands were folded over his chest, the fingers carefully interlocked. He had no family, no one to claim him. Just more refuse of the state that the taxpayers would no longer be burdened with.

There was a little mud and stick doll stuck between his knees.

Johnny’s eyes snapped open.

He began to speak about zombies in a dead voice, spinning out the last things his brain remembered. He clawed at his sheet, kicked his feet at the door. The drawer slid open then, Riker standing there.

“C’mon, boy,” he said somberly. “Nobody’s claimed you. Time to prepare your place…”

EMILY

When Emily came out of the grave, Mother was waiting there for her. She saw little Emily and began to immediately shake and sob. A broken cry came from her throat as the immensity of her daughter’s resurrection hit her. She went down to her knees in the sluicing muck, gasping and staring, her mouth unable to form words.

Emily just stood there, her white burial dress dripping wet and dark with graveyard soil that fell in clots. Even in the wan moonlight, her face was pale as tombstone marble, her eyes huge and black and empty.

“Emily?” Mother said, caught in some sucking, manic whirlpool of utter joy and utter horror. “Emily?”

Emily just watched her, completely indifferent to the scene. Raindrops rolled down her pallid face like tears. Finally, she grinned because it was what Mother wanted. She grinned and Mother recoiled like she had been slapped. Emily had not grinned in awhile and it came out a bit too crooked, a bit too toothy. “Mother,” she said, her voice dry and scraping like a shovel dragged over a concrete tomb lid.

Mother came forward, uncertain at first, but that endless week of mourning had drained everything from her and she could no longer see how this was wrong, how this was unnatural and insane. So she stumbled forward and collected Emily in her arms, squeezing her in the rain, paying no mind to the fetid stench that came off her daughter.

“I prayed for this, baby! I prayed and I wished and I hoped and I never, ever, ever lost my faith!” Mother said. “I knew you would come back! I knew you would come back to me! I knew you weren’t really dead!”

Emily did not hug her back.

In fact, the warmth of Mother’s fles

h slightly repelled her…even though the smell of it was appetizing. She felt Mother’s arms around her, but it did not move her. Emily came out of the grave with certain things, certain needs and desires, but love and affection were not among them.

But Mother did not see any of this and mainly because she did not want to. Grief had shattered her and mourning had laid her bare. The madness that comes with losing a child is a special madness, stark and numbing, seamless and all-encompassing. So Mother simply accepted. There was nothing more. Just acceptance.

Mother rambled on and on about how she had prayed and wished for Emily’s resurrection, how she had sat in her bedroom grim night after night after night, staring into the flame of a single candle and wishing her little girl alive again. And how last night she had dreamed that Emily had opened her eyes in the cloying darkness of her little pearl-white casket and that’s how she had known to come tonight with a shovel to set her baby free.

“But you weren’t dead, baby!” Mother said again and again. “I told them at the wake and I told them at the funeral and they wouldn’t believe me! They wouldn’t believe that my little girl wasn’t dead! But I knew! I knew! I knew you weren’t dead!”

“Yes, I was, Mother,” Emily said.

But Mother didn’t hear that either.

There were only her delusions now which were a high, sturdy brick wall that things like reason and decency could not hope to break through. She had her Emily back and that’s all that mattered, that’s really all that mattered. Emily was back…or something that looked like her was.

“Help me, baby,” Mother said, on her hands and knees, pushing wet earth back into the grave. “We have to cover this up so people don’t ask questions. You know how they ask questions. But I won’t let them take you away from me again.”

Zombie Pulp

Zombie Pulp